With Allen Huber “Bud” Selig announcing his plans to retire in January 2015, we can reminisce on the Seilg era, along with the other eight commissioners dating back to Judge Landis in 1921. They have played an important role in America’s pastime, holding down the fort during mischief and mayhem. They dealt with gambling, civil rights, free agency, and drugs. One which stands out the most is the 1919 Black Sox scandal which gave baseball its first commissioner. The owners gave the key to baseball to Judge Landis who banned eight Chicago players from the game for life. A.B. “Happy” Chandler had the entrance of Jackie Robinson. Ford Frick split Maris and Ruth’s homerun record. Kuhn was in office for free agency hearings in the US Supreme Court. Giamatti was around for the banning of Pete Rose. Finally, Selig had to handle the steroid era. These gentlemen were men of law, military, and business. Asked to come in and run it as such. All except for one, Mr. Ford Christopher Frick.

Born just one month and 19 days before the Babe, Frick joined the New York sports writing team in 1922. He became a lifetime baseball employee when he started covering the Bambino in 1923. Just like the rest of America, Frick fell in love with the larger than life ballplayer. This was a time when Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones owned the golf world, Jack Dempsey was the great boxing champion, tennis had Tilden, Lenglen, and Wills, and Notre Dame Football had the four horsemen in the backfield. Frick covered them all, but there was only one Ruth and he dominated the media. Baseball strategy prior to Ruth was “hit ‘em where they ain’t”, base stealing, and slashing led by Ty Cobb. The game changed because of Ruth and Frick covered it all from his Ruthian blasts to his boyish enthusiasm with fans and kids that never dimmed.

Born just one month and 19 days before the Babe, Frick joined the New York sports writing team in 1922. He became a lifetime baseball employee when he started covering the Bambino in 1923. Just like the rest of America, Frick fell in love with the larger than life ballplayer. This was a time when Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones owned the golf world, Jack Dempsey was the great boxing champion, tennis had Tilden, Lenglen, and Wills, and Notre Dame Football had the four horsemen in the backfield. Frick covered them all, but there was only one Ruth and he dominated the media. Baseball strategy prior to Ruth was “hit ‘em where they ain’t”, base stealing, and slashing led by Ty Cobb. The game changed because of Ruth and Frick covered it all from his Ruthian blasts to his boyish enthusiasm with fans and kids that never dimmed.

“Attempting to measure Babe Ruth’s greatness by standard rule, or mathematical formula, is like trying to thread a needle while wearing boxing gloves.” – Ford Frick

From the end of WWI until the great depression was considered the golden age of sports by most writers in that time. It was an era of laughter and excitement when America supposedly won the “war to end all wars.” For Frick it was an opportunity to cover sports as they grew internationally, but also to cover some of the greatest baseball players of all time. Of the first 108 players elected into the Hall of Fame, 52 of them played during the postwar decade. Names like: Dickey, Sisler, Gehrig, Foxx, Hornsby, Cronin, Cobb, Ruth, Speaker, and Combs; along with pitchers such as: Walter Johnson, Left Grove, Dazzy Vance, and Grover Alexander.

Judge Landis authorized the broadcasting of the World Series in 1921, which would change radio forever. The first broadcast was done by New York’s WEAF, however it would blow up in Chicago when Mr. Wrigley let all local stations broadcast Cubs games. Public interest in nearby states for the Cubs took off. WOR began broadcasting the same year Frick came to New York in 1922. The first two years of WOR, operation came out of Bamberger’s department store which sold radio sets to consumers. It wasn’t until 1924 that they had their own station. In 1930 Frick went from being a writer to becoming a broadcaster. The first local New York broadcast took place in 1931 when four local stations were invited to broadcast a game at Ebbets Field. Frick along with Ted Husing, Sid Loberfeld, and Graham McNamee sat in a box behind the plate and talked into microphones hooked up by telephone lines with one technician on hand that had the job of keeping the lines open. The fan mail poured in and the radio business would boom. Frick called the final regular season series between the Cardinals and Dodgers which decided the pennant. The Cardinals went onto win and that was as close as Dazzy Vance ever came to a world series, but it did attract a record listening audience. By the mid 1930’s, all sixteen teams were broadcasting their games. It opened up a source of income that television would soon quadruple.

1934 would be a big jump for Frick as he was elected Director of the National League Service Bureau at the beginning of the year, then National League President before Thanksgiving. What he is most known for during his time at the head of the National League is the working with hotel owner Stephen C. Clark in creating the National Baseball Museum in Cooperstown New York. Clark bought a ball for $5 in 1935 that was used by youngsters in games played at Phinney pasture during the mid 1800’s. The ball was found in a trunk, blackened, torn, patched with ancient letters on it. Clark mounted the ball and displayed it through the Otsego County Historical Society which then attracted local interest. Clark then added his own prized baseballs, paintings, and prints. He would send his staff across the country to collect other baseball artifacts to add to the collection. Within a year, his small library became a place to travel. Although the Hall of Fame opened in 1939, the first induction class came in 1936. Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Ty Cobb, and Honus Wagner were elected. 1939 means something even more because it celebrates the 100th anniversary of the “Myth” of Abner Doubleday creating the game of baseball in Cooperstown in 1839.

From celebratory to controversy, Frick would later have to face the dispute of the first black player coming into his league. Happy Chandler was commissioner of baseball; however Jackie was going to play for the Dodgers of the National League. It was not unexpected as Robinson was assigned to Montreal the year before. Branch Rickey was a man who did not act on impulse. The idea of integrating blacks in the majors goes all the way back to the mid 1930’s, but no one could ever pull the trigger. In 1947, Frick dealt with all problems big and small with Jackie Robinson. It started with spring training in the south, hotels and restaurants, and also opposing teams. The Cardinals, now one of the classiest organizations, was one of the toughest to deal with as they set out to protest their games against the Dodgers. Frick accepted the entrance of Robinson and other black players to follow. He would then go on to warn organizations of possible suspensions for those who chose to dispute.

“I cannot but feel that the one man, above all others, who deserves the eternal thanks of his own race, and all thinking people, for bringing about baseball’s greatest reform, is Jackie Robinson himself…Certainly baseball people should be eternally grateful for the contribution he made to his own people, and to the game.” – Ford Frick

Brooklyn would bring up Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe the next year, both competitors and gentleman. Robinson was no longer a one man crusade, although he paved the way for other greats to come.

Happy Chandler would retire from being Major League Baseball’s commissioner in 1951, giving the reigns to Ford Frick who has been in the game since the early 1920’s as a journalist following the Sultan of Swat. The 50’s was all about the expansion west. There were meetings with the Pacific Coast League about turning the PCL into a third circuit and compete against the American and National Leagues which only went as far west as Chicago. This was immediately discouraged, however San Francisco and Los Angeles pledged ready to take on a major league team. The plan was to advance individual cities to major league status, expanding the geographic of the baseball, but keeping eight teams to each league. The Braves were the first to go in 1953, taking off for Milwaukee. Although Boston fans were bitter, they still had their Red Sox. The following year the American League had two changes. The Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City while the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore. The major leagues expanded from 10 to 13 cities. Things then got dicey in 1957 with two New York teams traveling across the country. The Dodgers went to Los Angeles and the Giants took to San Francisco. Fans were appalled and in uproar over this massive change. New York had become a one-club city.

Immediately after, the major leagues would expand to 10 teams each. New York, Houston, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis were selected. A territory rule would be stepped on with two teams playing in New York and two in Los Angeles. A long meeting with league leaders in St. Louis and with Frick as commissioner went back and forth until Mr. Ben Fiery of the American League proposed that no city could be shared between clubs if the city population is less than 4 million. After agreement, Yankees and Mets would share the Polo Grounds until Shea Stadium was built, and the Angels would temporarily use Wrigley Field in Los Angeles.

“Baseball has always been slow to accept change. Only through dire pressure can any radical change be accomplished. The move of the Giants and Dodgers from New York to California brought that pressure in abundance.” – Ford Frick

The last major historic event that took place while Frick was involved with baseball was the homerun race to catch Ruth’s 60 by Roger Maris during the same year of the expansion of two more teams in each league in 1961. Along with the expansion of the leagues was the extension of the season from 154 games to 162. On the 154th game of the season for the Yankees, Maris had 59 home runs. It wasn’t until September 26th when Maris his number 60 to tie Babe Ruth’s record. On October 1st, the last day of the season, Maris hit home run number 61 to break the record, but in 162 games. Frick would separate the two records, not giving full credit to Maris for having the new record. Some say it was because Frick was such a fan and good friend of Ruth’s he would have none of it. Players such as Roger Hornsby backed Frick comparing Ruth’s .356 average in 1927 and Maris’ .269 average in 1961. Either way, Frick did what he thought was right for the game.

“The commissioner is in a tough spot…He cannot flaunt national law. His decisions must be tempered to fit the times. He cannot roll in the mud of a labor argument one moment, and next moment don a clean shirt and assume authority as final judge and arbiter. As commanding general his job is to develop strategy to win the war, not to man the skirmish lines or lead a scouting patrol…The fact is the commissioner is a hardworking executive trying as best he can to weld scores of individual enterprises into a national institution for the purpose of providing honest competitive entertainment for a sports-minded public.” – Ford Frick

Ford Frick is the only commissioner to be built from within. He is a prominent figure in baseball history as he’s been at the forefront from radio beginnings to Astroturf. The integrity of the game was held strong during his time in office as he paid tribute and respect to the past, but also was a pioneer in the movement and expansion of the game. No one else was as heavily involved in the revolution of baseball as Ford Frick. He was also a fan of the game, its players, and its followers.

Frick’s Players List

Happiest Player: Ernie Banks – His “nice day for a game” is a personal trademark

Most Aggressive Player: Ty Cobb – His every move was a challenge

Player with Greatest Fan Appeal: Babe Ruth – Undoubtedly

Greatest Pitching Performance: Don Larsen’s Perfect Game – vs Dodgers on October 8, 1956

Best World Series Performance: Brooks Robinson – Greatest individual exhibition I ever witnessed

Greatest World Series Thrill: Bill Mazeroski – 9th inning home run in 1960 game 7 World Series

Favorite “Bad Boy”: Frankie Frisch – I fined him and suspended him the most

*Credit for quotes: Frick, F. (1973). Games, astrisks, and people; memoirs of a lucky fan. New York, NY: Crown Publishers Inc.

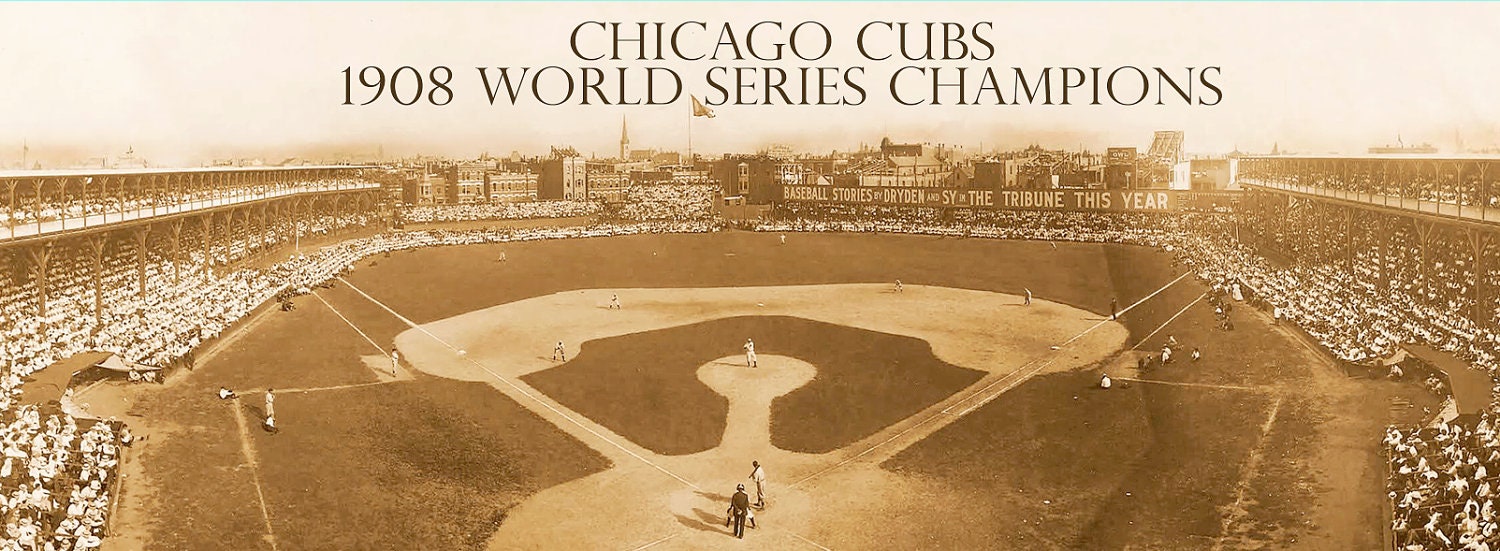

The following year, the Cubs and Tigers would face-off in a

rematch in the 1908 World Series, with Ty Cobb looking for revenge. The Tigers

had game one in their paws up 6-5 going into the top of the ninth, but the Cubs

would hit six straight singles to score five runs to win the game. The first

three games was an offensive outburst compared to the 1907 World Series with

the Cubs scoring 19 runs to the Tigers 15. With the Cubs up 2-1, the series

would head back to Bennett Park in Detroit. Mordecai Brown and Orval Overall

would throw back-to-back shutouts against Detroit, neither giving up more than four

hits to finish out the series. Orval Overall would be the first pitcher to

strikeout four batters in an inning, and game 5 would be recorded as the

smallest crowd to ever attend a series game with 6,210 paid attendees.

The following year, the Cubs and Tigers would face-off in a

rematch in the 1908 World Series, with Ty Cobb looking for revenge. The Tigers

had game one in their paws up 6-5 going into the top of the ninth, but the Cubs

would hit six straight singles to score five runs to win the game. The first

three games was an offensive outburst compared to the 1907 World Series with

the Cubs scoring 19 runs to the Tigers 15. With the Cubs up 2-1, the series

would head back to Bennett Park in Detroit. Mordecai Brown and Orval Overall

would throw back-to-back shutouts against Detroit, neither giving up more than four

hits to finish out the series. Orval Overall would be the first pitcher to

strikeout four batters in an inning, and game 5 would be recorded as the

smallest crowd to ever attend a series game with 6,210 paid attendees.